Here's How Much Money You Need for Bankers to Think You're Rich

In an era of hyper-wealth, economy-class rich starts at $25 million.

Just how rich is "rich?"

The answer, of course, depends on who's asking—and these days, many are.

In rich-tropolises such as New York and London, 1 percenters moan that living on $500,000 a year feels Dickensian. With a pot of $40 million—and private schools, a Hamptons retreat, a horse and a charity to feed—a hedge funder on the Showtime drama "Billions" exclaims: "F---! I'm broke!"

Here, then, is a real answer, courtesy of the hush-hush world of private banking: $25 million.

Twenty-five million dollars in investable wealth. The kind of money you could afford to see dip into the red for a quarter or three, maybe even a year or two, without breaking a sweat. With $25 million, maybe, just maybe, you're starting to be rich.

Because in this era of hyper-wealth and hyper-inequality, that is simply where rich begins—a ticket, in truth, to the first, lowly rung of rich. For most of the planet, $25 million represents unfathomable wealth. For elite private bankers, it buys their basic service.

Call it economy-class rich. Business class? That's $100 million. First class? $200 million. Private-jet rich? Try $1 billion.

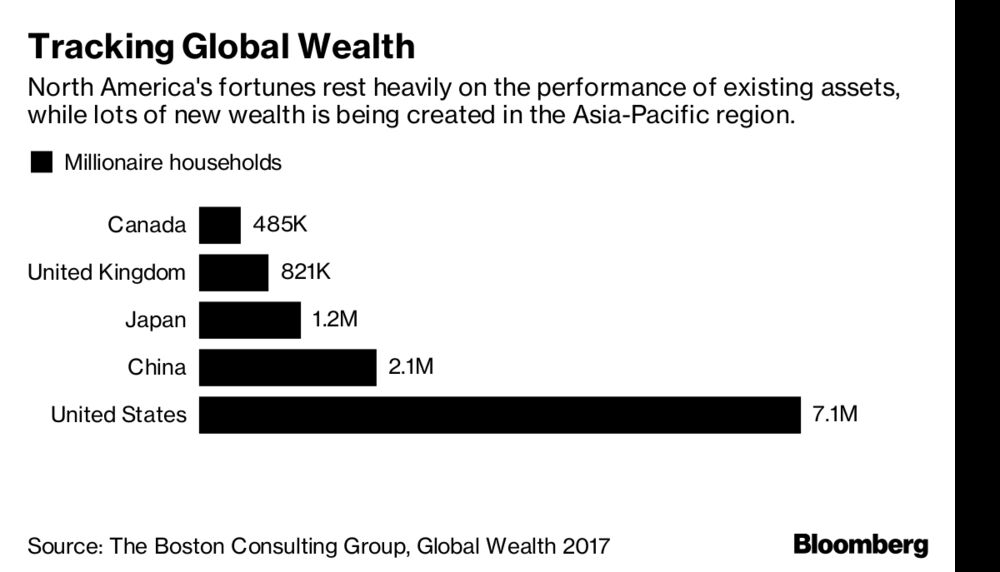

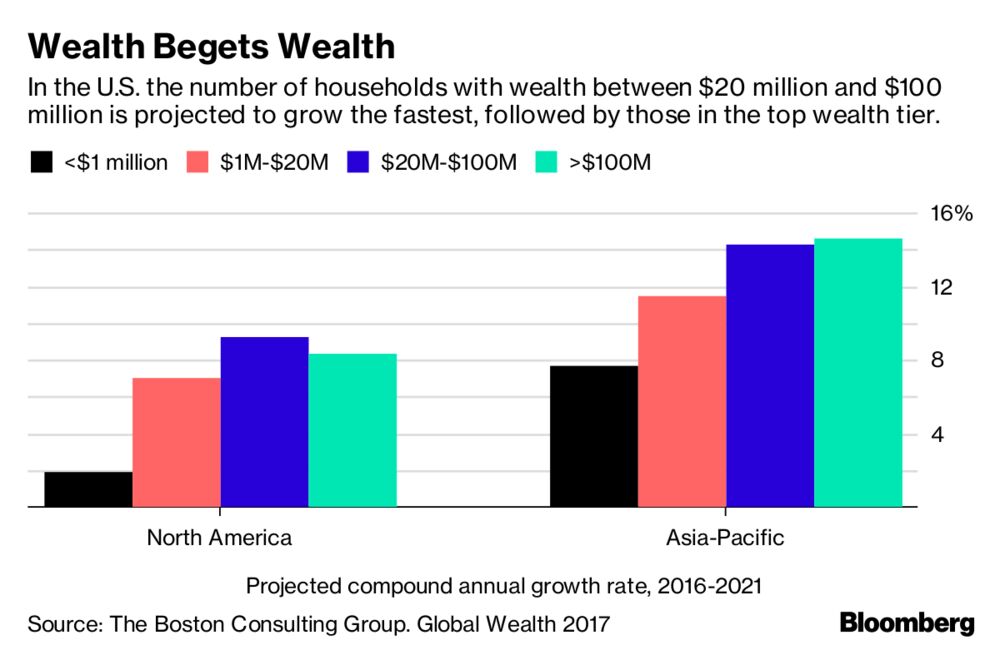

We all know the wealth gap between the rich and poor, and the rich and the really rich, is only getting wider, due in large part to the bull market in stocks and wealth generated in private businesses around the world.

What may be less apparent, at least outside financial circles, is what all that money is worth to the bankers who discreetly tend those fortunes.

No private bankers worth their wingtips will say they don't care about clients with "only" a few million. Northern Trust Corp., which works with many of the world's richest families, stresses that in recent quarters more than 50 percent of new clients have had investable assets in excess of $10 million. But "to get the highest level, companies have raised the bar," said Brent Beardsley, who leads Boston Consulting Group's work in asset and wealth management globally.

The measure of what makes someone rich has changed dramatically in the past two decades. In 1994, when Peter Charrington, global head of Citi Private Bank, first joined the firm, "Three million was largely considered ultra-high net worth across the industry," he recalled. "Fast-forward almost 25 years, and $25 million is how we define ultra-high net worth."

Wealth managers like to frame the type of client they target in terms of the services needed. For example, a married couple with an estate valued well below $22 million, held largely in a diversified portfolio of publicly traded stocks, may not need a lot of fancy trusts-and-estates work, since about $22 million can go to heirs without worrying about estate and gift taxes. (That $11.18 million per person is up from $5.49 million in 2017, and sunsets in 2025.)

A much wealthier family with homes and assets in multiple countries and currencies might require more cash flow management, customized financing for mortgages, yachts or planes, and the ability to borrow against art or investment portfolios. It may make sense for a client to house business interests in a trust, with the adviser as trustee.

At a private bank with an investment banking arm, "sometimes the investment bank collaborates with the private bank client in doing a recapitalization of the company, or maybe sells a non-core division to create liquidity so a family member can exit the business," said John Duffy, global head of Institutional Wealth Management for J.P. Morgan Private Bank.

"Getting rich is complicated," said Steven Fradkin, president of wealth management at Northern Trust. "It's just a good complication to have."

Placing investable assets of at least $25 million with a wealth manager—and clients with that amount or more tend to work with a few firms—can bring access to initial public offerings, and having at least $5 million in investments moves a client past one regulatory hurdle to taking part in private offerings.

Elite wealth managers invite clients to networking events where they can mingle with like-monied clients.

Not long ago, the actress Lucy Liu, of "Elementary" fame, spoke at an intimate dinner held for wealth advisers and clients of UBS Wealth Management USA. At UBS's annual Philanthropy Forum for clients, held in 2017 at the Fairmont San Francisco hotel, Andre Agassi spoke about his impact investing, as did UBS client and former Goldman Sachs Group Inc. partner Mike Novogratz and his wife Sukey. In 2016, Hilary Swank, Adrian Grenier and Kimbal Musk (Elon's brother) were brought in to speak at restaurant Blue Hill at Stone Barns; the non-profit Stone Barns Center was founded by late philanthropic giant David Rockefeller and his daughter Peggy Dulaney.

That's not to say $25 million opens all doors. Abbot Downing, Wells Fargo's operation for ultra-high-net-worth families, works with clients who have at least $50 million in investable assets or $100 million in net worth. Ascent Private Capital Management of U.S. Bank sets what Martim de Arantes Oliveira, regional managing director for its San Francisco office, calls a "stake in the sand" at $75 million in net worth for multigenerational wealth. There will always be exceptions—for the family friend or a promising entrepreneur.

Competition for those fortunes is fiercer than ever. Much of investing has been commoditized, assets have poured into low-cost passive investment products and clients burned in the 2007-2008 crash are focused on preserving wealth, rather than taking investment risk. Costs of regulation, technology and talent have risen, even while fees are under pressure. Top relationship managers have been leaving companies to set up their own shops, and clients tend to be loyal to people over companies.

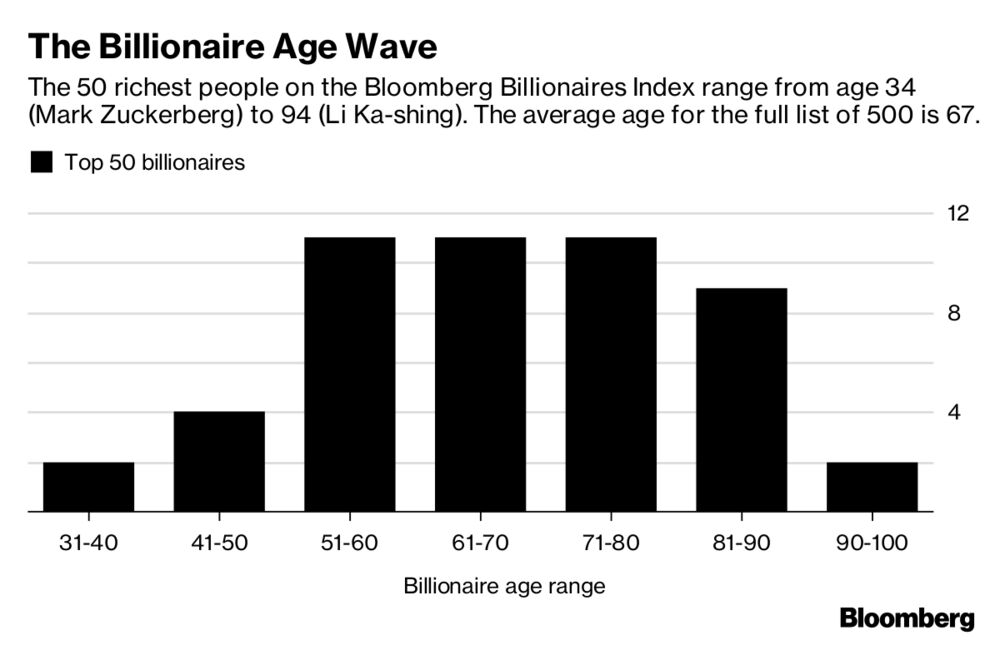

All the while, with matriarchs and patriarchs aging, wealth managers are working to sell them on "softer services" such as family governance and strategies for philanthropy, said Donnie Ethier, director of wealth management at Cerulli Associates. "Two-thirds of high-net-worth investors and up [in wealth] are now over age 60, and in many cases the real concentration of wealth is with people above 70," he said. Of the 50 richest people on the Bloomberg Billionaires Index, about three-quarters are over age 60, and 34 percent of those are over 80. The 30-somethings in the top 50: Mark Zuckerberg, 34, and China's Yang Huiyan, 37.

Wealth managers are working hard to connect with what one called "G2s, G3s, G4s"—younger generations of existing clients—and to pull in new entrepreneurial wealth. So it makes sense that, when you step onto the 21st floor at Ascent's San Francisco office, you aren't greeted by banks of mahogany-paneled walls and oriental carpets. The light-filled space features primarily glass walls, sleek white furniture, art from local galleries, and a view overlooking the water of the East Bay, with Treasure Island in sight. If Apple Inc. made furniture, it would feel at home there.

In a sign of the times, Ascent's offices include a family room where client babysitters sometimes entertain kids while older family members meet in the learning lab. ("Board room" sounds so boring.) Ascent's historian might present a snippet of family history using old photos and, to make it fun for kids, stage an Easter egg hunt whose eggs hold a small amount of money, along with a bit of family lore in a picture of, say, their grandparents with their first car. (High-end wealth managers employ lots of historians; Abbot Downing hired the senior historian for the American Girl doll franchise last year.)

How much might all of that cost a client? Fees can vary widely within and across firms. Wealthy people with less than $100 million might pay from 50 to 100 basis points, said Peter Rup, chief executive officer of New York-based Artemis Wealth Advisors, an independent registered investment adviser. With an account above $100 million, a client could pay roughly 40 basis points, and over $200 million, around 25 to 30 basis points for investment advice, he said.

At several hundred million dollars, opening a single-family office can start making more sense. Northern Trust's Fradkin said that as some fortunes reach $500 million to $1 billion or more, some clients set up their own offices—but, he added, they still turn to the bank a lot.

More families are opting to join multifamily offices. Pooled resources bring more access to deals, economies of scale and fewer conflicts of interest from advisers eager to cross-sell products. Multifamily offices may charge a minimum annual fee. At Boston-based TwinFocus Capital, which advises on about $4.5 billion in assets, the minimum fee is $250,000, said Paul Karger, who co-founded the firm with twin brother Wesley in 2006. The stated minimum is $50 million in balance sheet assets, but Karger really wants more than $100 million. It makes more sense, given the costs—the largest of which is labor, he said, since to recruit and retain top talent compensation must cost well above industry averages.

It's direct investment in companies and buildings where the line between the rich and seriously wealthy is most pronounced. "This is a threshold differentiator among the world's wealthiest, compared to the merely very wealthy, let alone the 401(k) investor," said J.P. Morgan Private Bank's Duffy. "These very large families are investing in private companies, owning a percent of the company versus a share of a public entity."

To meet that need, private banks and multifamily offices may offer clients access to direct investments in private companies. Some private bank clients have invested directly in luxury spin franchise Peloton Interactive Inc., said Duffy, through a partnership between the investment banking arm and the private bank. Clients also invested alongside big institutional investors in the Topgolf franchise.

In the end, the most elite wealth managers are able to provide a level of analysis and services so that very complicated financial lives become manageable. A trusted adviser should lead to that most priceless of outcomes, which can justify about any fee: peace of mind.

— With assistance by Simone Foxman

Read the full article here:

Read the full article here: