Commodity tycoon Lukas Lundin expects oil to hit US$100 on global capex cuts

If Monopoly were played for natural resources, Lukas Lundin would be the natty gent in the tuxedo — riding a motorcycle.

And like many with a knack for the board game, the Swedish-Canadian tycoon says his victories are as much about guts as a good roll of the dice.

"You make your own luck," the 58-year-old Lundin said in an interview at his Vancouver offices last week. "If you sit at home, you're never going to get the luck."

No one could accuse Lundin of lazing around the house. He and his younger brother, Ian Lundin, oversee a family fortune estimated to be worth at least US$2.5 billion, according to the Bloomberg Billionaires Index, a number Lundin said is about right. The Lundins own stakes in companies across the globe, holding commodities from industrial metals, gold and diamonds to oil, uranium and Latin American cattle. And they're not done yet.

"It's a good time to acquire right now," Lundin said from his office overlooking the cargo ships and sparkling waters of Burrard Inlet.

The best opportunities are in base metals and he's keen to see Lundin Mining Corp., of which the family owns about 13 per cent, resume its acquisition spree. The company bought a controlling stake in Freeport-McMoRan Inc.'s Candelaria/Ojos del Salado copper operations in Chile in 2014 and the Eagle nickel and copper mine in Michigan from Rio Tinto Group in 2013.

"For Lundin Mining, I think we have to find another large asset so we have a good growth story," he said. Meanwhile for Lundin Gold Inc., a new addition to the portfolio that has only one asset, "Ideally we'd find another high-grade gold deposit somewhere."

The company looks to buy assets, preferably developed, in a down cycle and unlock value. A rally in base metals hasn't really gained traction yet, meaning that's where the best opportunities lie, Lundin said. By comparison, gold has surged 25 per cent this year, making it "harder" to find the ideal asset to buy.

HandoutAn overview of Lundin Mining's Zinkgruvan Zinc, Lead and Silver Mine, in central Sweden.

Best Bet

Lundin said zinc could be the best-performing commodity in the next two to five years, while copper and nickel will take a bit longer. The ideal base-metal acquisition would be in Chile, Argentina or Peru, countries in which Lundin is comfortable doing business, he said.

"Bigger is better," he said, when asked what size asset he's hunting for. With borrowing costs low, he'd consider taking on more debt for a big purchase.

That, he said, needs to be balanced against the fact that both he and Lundin Mining Chief Executive Officer Paul Conibear are keen to pay shareholders a dividend as soon as cash flow makes that sustainable. "We can pay a small dividend, I think, and at the same time have a fairly good acquisition."

What Lundin companies won't do is borrow money to fund dividends. "That's crazy stuff," he said.

Issuing equity to fund a base-metals acquisition would be an option, but not until Lundin Mining's stock price is much higher. Asked if he'd consider a 10 or 20 per cent improvement as enough, he scoffed: "One hundred per cent! I'm not here for 10 or 20 per cent."

Oil at US$100

Crude could return to US$100 a barrel because the two-year market downturn has curbed investment, according to Lundin, who is also a member of Lundin Petroleum AB's board.

That kind of price rebound won't be good for the industry, said Lundin, a member of the billionaire Swedish family with interests spanning oil and solar energy to diamonds and gold.

"I think between $50 and $80 is probably better for our business," Lundin said in an interview. "It keeps it more stable and all the good projects would work."

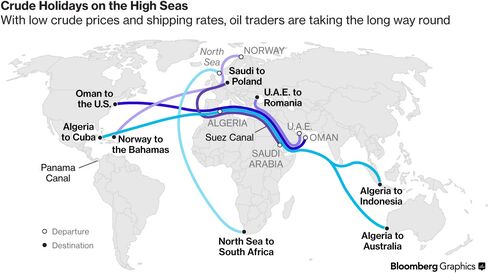

Oil has gyrated five times between bull and bear markets this year, with benchmark Brent crude moving between a high of $52.51 a barrel and a 12-year low of $27.88. Companies across the industry are slashing spending for the 2015-to-2020 period by US$1 trillion, according to consulting firm Wood Mackenzie Ltd.

This means crude supplies will start to dwindle in as little as two years, potentially boosting prices, according to Norway's Statoil ASA.

Except during the financial crisis in 2008, average Brent prices increased every year from 2002 to 2012, and topped US$100 a barrel from 2011 to 2014. That persuaded companies to embark on higher-costs projects, building capacity that outstripped demand and led eventually to a collapse in prices.

Lundin expects prices to be US$60 to US$70 a barrel in the next nine months. Brent will average US$55.50 next year and US$62.25 in 2018, according to the median of analyst estimates compiled by Bloomberg. Only one of the 18 analysts with forecasts for 2019 expects prices higher than US$100.

Extreme Pursuits

"No guts, no glory" is the family motto and it's clear Lukas Lundin takes it to heart. A four-time motorcycle competitor in the Dakar rally, he's also climbed Mount Kilimanjaro twice.

He has no plans to retire: "My job and my hobby's all the same so I don't really know what retirement means." It's possible one of his four sons could helm the empire at some point, he said, but only if he's the best person for the job.

The family meets once a month to discuss its holdings, which have become so extensive Lundin confesses he doesn't know their exact number. "It's a bit scary," he said. "There are too many companies." He would like to consolidate them, ideally into six or seven — from 12 now, according to a spokeswoman — either by merging or selling them.

Darryl Dyck/BloombergLukas Lundin, chairman of Lundin Gold Inc.

Finding Treasure

It might make sense, for example, to have just one oil company, he said, and at some point the family probably will sell its renewable-energy business. Given that Lundin Petroleum AB, whose board is headed by his brother Ian, expects to double or triple production in the next five or six years, it's unlikely to do more energy acquisitions, he said.

The Lundins have a reputation for finding treasure where others have passed it by, including billions of barrels of oil in Norway, at an area that had been drilled without success, and golf-ball sized diamonds at a mine in Botswana sold by De Beers.

In the case of Fruta del Norte, Lundin Gold's sole asset, he said the company was able to forge inroads with the Ecuadorean government where the asset's previous owner, Kinross Gold Corp., had been stymied.

The Lundin companies also have had some success selling assets near their cycle peak. The family owned a small stake in Red Back Mining Inc. in 2010 when it was sold for about US$8 billion to Kinross, which later booked billions of dollars in writedowns.

It could seem like a Midas touch, if not for mistakes. Lundin admits his worst was in 1995 following the sale of mining company International Musto Explorations Ltd., which netted a 1,757 per cent return to investors, according to the Lundin Group's website.

Flush from that victory, he bought assets in Mexico and tried to apply the same blueprint — but overspent and then failed to find a buyer as the project looked less and less feasible. The stock fell from $16 to 20 cents, he said. It was a hard lesson on assessing each deal on its own merits.

Today, Lundin Mining executives are considering what to do with the company's 24 per cent stake in the Tenke Fungurume mine in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The issue has arisen because its partner on the copper-cobalt operation, Freeport, struck a deal to sell its 56 per cent share to China Molybdenum Co. in May.

Lundin executives are in discussions with Freeport and the Chinese to decide whether to sell or keep their stake, or to exercise a right of first offer, allowing it to match the Luoyang-based company's bid.

China Molybdenum would likely be "OK" as a partner "but it's a different culture and they're not very experienced miners so I'm sure it's going to be more work for us," Lundin said. If Lundin Mining exercises the right, which would give it 80 per cent of the mine, it could also decide to sell its entire stake, pending approval from the government, he said.

The mine has a long connection to the family and was important to his father Adolf, who purchased a 55 per cent stake in 1996 after convincing then-President Mobutu Sese Seko to do the deal. But if Lukas Lundin gives short shrift to the notion of luck, he's equally dismissive of nostalgia, saying there isn't a single asset the company would not consider selling for the right price.

Family Legacy

Adolf Lundin died in 2006 but his influence is ever-present in the family business. Last Thursday, a crew was in house to film a documentary for the family about his achievements. It's a legacy not without controversy. Lundin Petroleum has come under criticism over allegations that its presence in Sudan — begun under Adolf's watch but continued under his sons — contributed to human-rights violations during decades of conflict.

The brothers have maintained that their business in Sudan offered economic and social benefits to the local population, and deny the allegations. Lundin Petroleum has had no financial presence in Sudan since 2009. "It's pretty tough to have the prosecutor general in Sweden chasing us for the last seven years," Lundin said. "They want to prove we've committed war crimes. Of course it's quite unpleasant."

Photographs of Adolf, and other family members, are found throughout the office, along with the mementos of more than four decades of global deal making. "Tombstones" — the mark of a successful close — hang on the walls and sit on shelves. It's the office of an empire builder: There's a massive globe on the floor and a huge world map mounted behind Lundin's desk.

"Ninety percent of our assets are still in resources but I think, over time, we'll probably divest a bit," he said. "We'll probably become bigger in commercial real estate in Switzerland, which is very profitable."

Shades of Monopoly again — and the game's board keeps getting bigger. "We've changed a lot in 10 years," Lundin said. "Hopefully 10 years from now we're three to four times the size we are today."